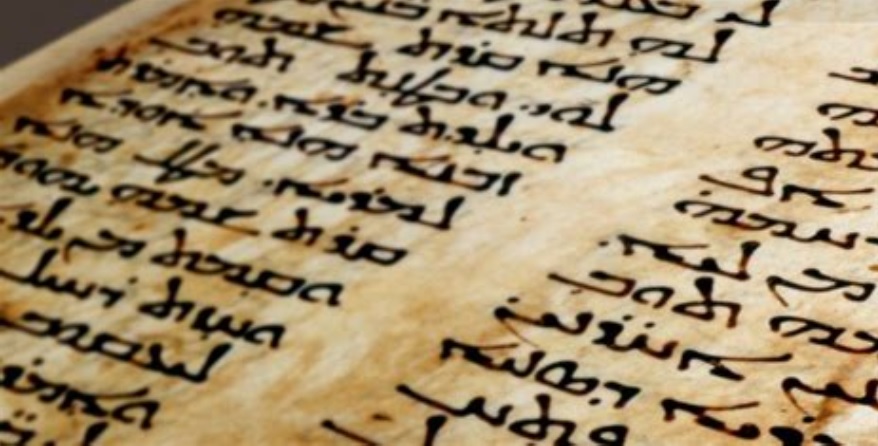

The Old Testament portion of the KJV rests upon the Masoretic Text, a Hebrew tradition meticulously preserved by Jewish scribes known as the Masoretes from the 6th to 10th centuries AD. This text represents the culmination of an even older lineage, stretching back to the autograph writings of Moses, David, and the prophets. The Masoretes, working in Tiberias and other centers in the Galilee region, added vowel points, accents, and marginal notes (masorah) to ensure the exact pronunciation and interpretation of the consonantal Hebrew text, which had been copied letter-by-letter since the time of Ezra the scribe around 450 BC.

The preservation of the Masoretic Text was no mere academic exercise; it was an act of devotion amid diaspora and danger. After the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70 and the Bar Kokhba revolt in AD 135, Jewish communities scattered, facing Roman persecution and later Byzantine and Islamic conquests. Scribes like the Ben Asher family in Tiberias labored under threat, producing codices that became the standard. The Aleppo Codex (c. AD 930), once housed in the Great Synagogue of Aleppo, Syria, and the Leningrad Codex (AD 1008), preserved in St. Petersburg, Russia, are prime exemplars. These manuscripts demonstrate extraordinary fidelity: the Leningrad Codex matches earlier fragments like the Dead Sea Scrolls (c. 250 BC–AD 68) in over 99% of cases, with differences limited to spelling or minor orthographic variations that do not affect meaning.

The Aleppo Codex, a key Masoretic manuscript from c. AD 930, showcasing the precision of Hebrew preservation.

The Masoretes' rules were rigorous: a scribe could not write even a single letter from memory but must copy from an existing scroll, counting letters and checking for errors. If a single mistake was found, the entire manuscript was destroyed. This system ensured that the text of Isaiah 53, prophesying the suffering Messiah, remained unchanged from the first century BC to today. As David W. Daniels notes in his works from Chick Publications, the Masoretic Text's uniformity across thousands of medieval manuscripts far surpasses the textual stability of secular works like Homer's Iliad, which has over 2,000 variants in its earliest copies.

The New Testament: The Byzantine Text-Type and Its Enduring Witness

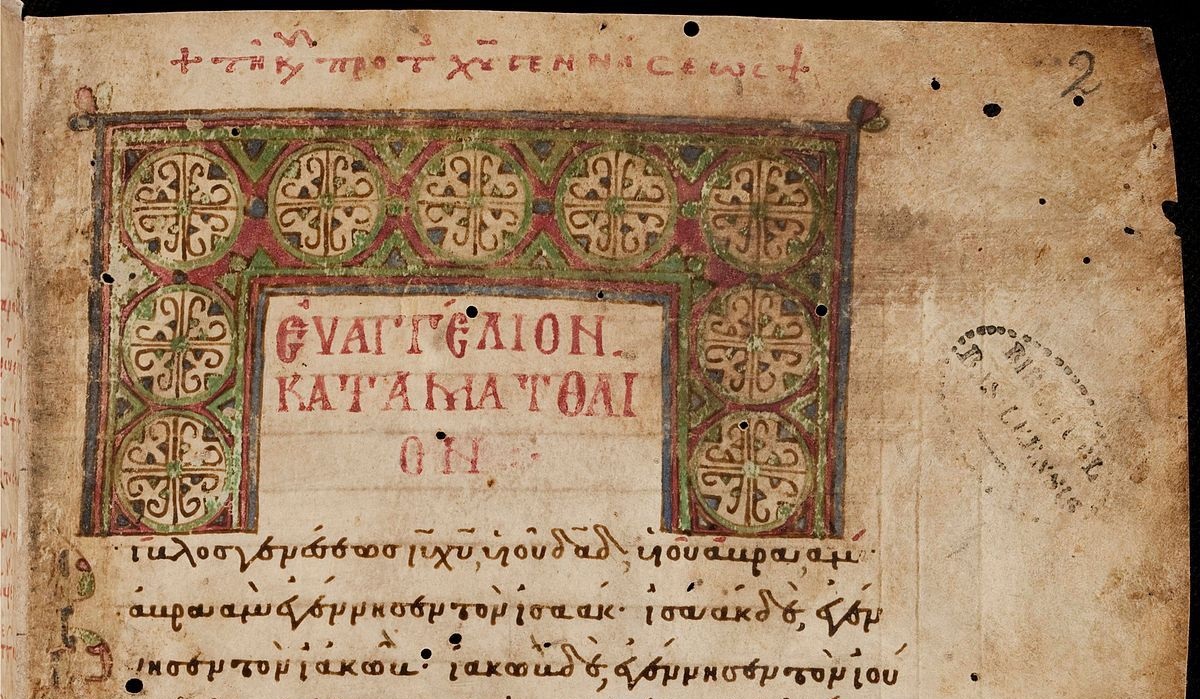

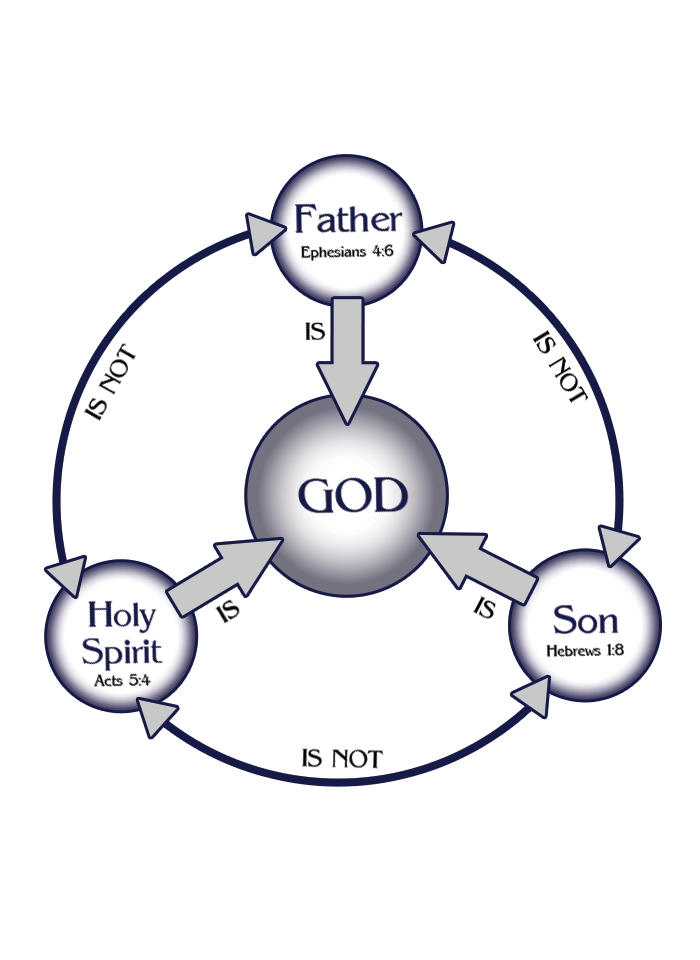

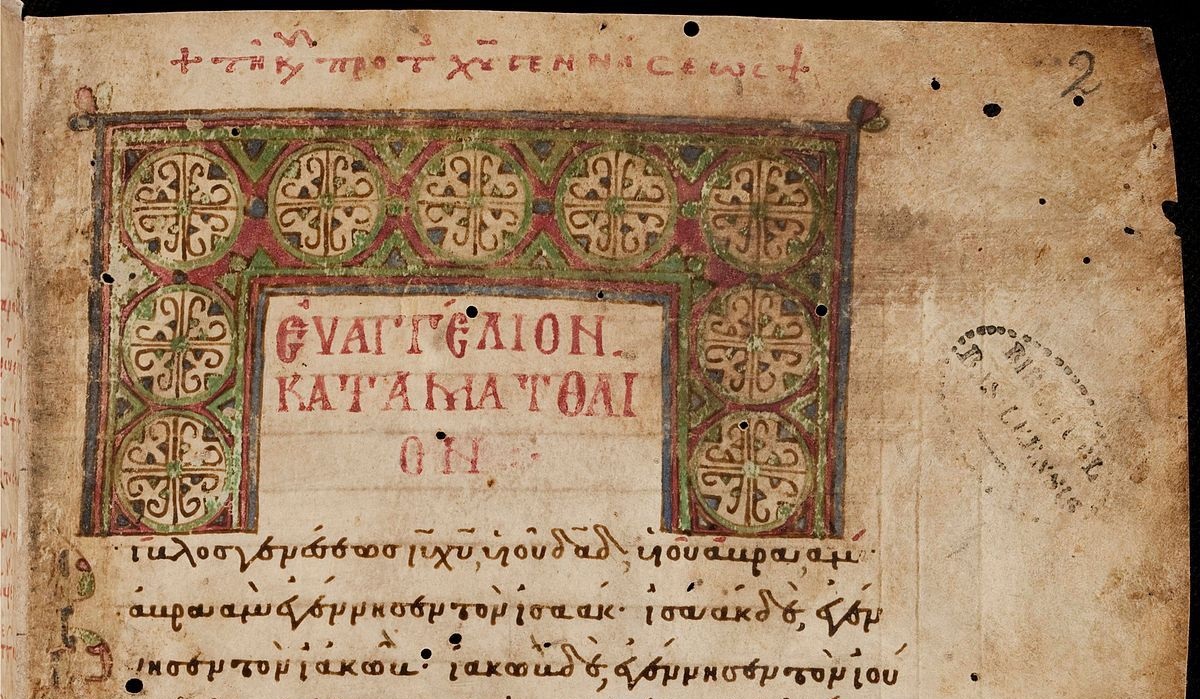

Turning to the New Testament, the KJV draws from the Byzantine text-type, also called the Majority or Traditional Text, which forms the backbone of the Textus Receptus. This textual family, used by the Eastern Orthodox Church for over 1,000 years, boasts over 5,000 Greek manuscripts—95% of all extant Greek New Testament copies. These include uncials (majuscule script) from the 4th century onward and minuscules (cursive script) from the 9th century, but evidence traces back further.

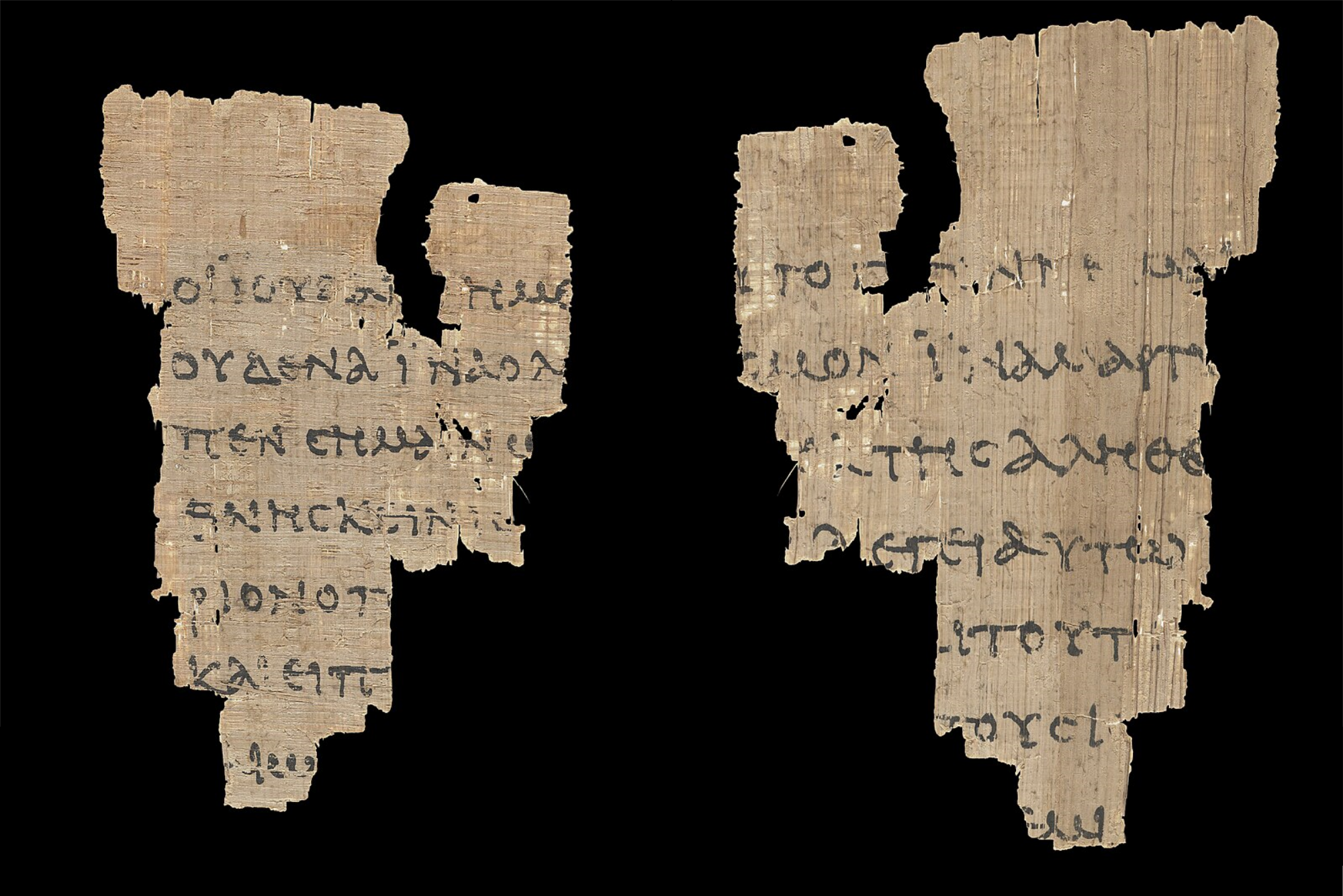

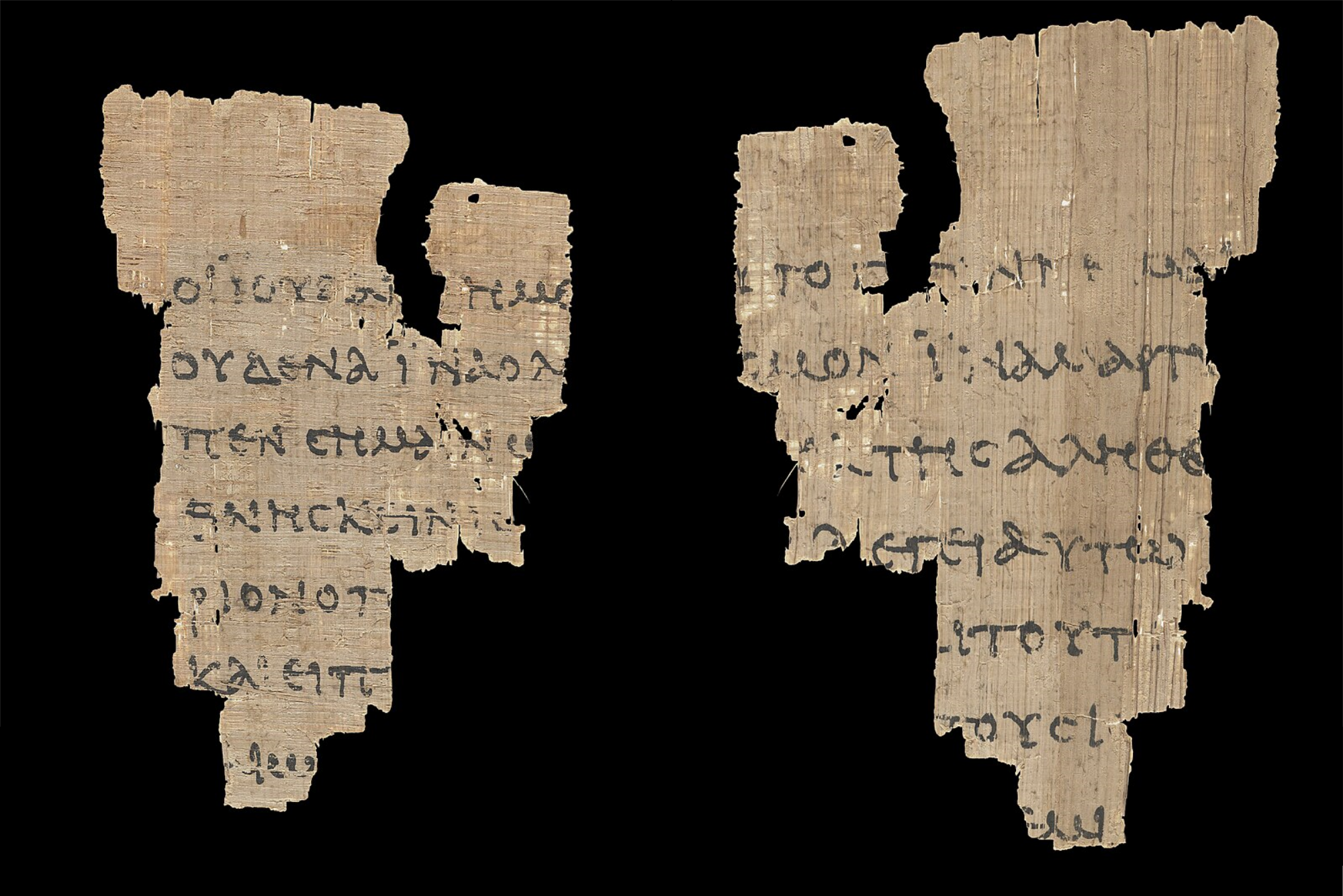

Early patristic quotations from church fathers like Irenaeus (AD 130–202), who quoted the Byzantine form in Against Heresies, and Origen (AD 185–254), whose Hexapla inadvertently preserved Byzantine readings, confirm its antiquity. Contrary to critics claiming the Byzantine text originated in the 4th century, sites like logosresourcepages.org document pre-Constantinian witnesses, including Papyrus 46 (c. AD 200), which aligns closely with Byzantine readings in the Epistles. Dean John William Burgon, in his exhaustive collations, argued that the Byzantine text was the "traditional text" of the apostles, circulated widely in Antioch, the church's early hub (Acts 11:26, KJV).

The agreement among these manuscripts is staggering. Burgon examined hundreds and found that in the Gospels alone, random pairings agreed in 99.75% of verses, with variants mostly in word order or spelling—never doctrine. Across the entire New Testament, the Byzantine family exhibits a uniformity rate of over 99%, as detailed in Gail Riplinger's New Age Bible Versions, where she collates thousands of readings to show the Received Text's stability. This harmony is evident in key passages like the longer ending of Mark 16:9-20 and the Johannine Comma (1 John 5:7), affirmed in over 1,800 Byzantine manuscripts.

These manuscripts were not hoarded in monasteries but copied for churches across the Byzantine Empire, from Constantinople to Mount Athos. Their proliferation—far outnumbering Latin Vulgate copies—ensured redundancy against loss.

Persecution and the Blood of the Martyrs: Preservation Through Fire

The transmission of these texts was secured not by imperial decree but by the blood of martyrs. From the first century, Roman emperors sought to eradicate the Scriptures. Nero (AD 54–68) blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome, ordering them burned alive or thrown to beasts, as recorded in Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna (AD 155), was burned at the stake for refusing to deny Christ, his final words echoing Revelation 2:10 (KJV): "Be thou faithful unto death." Under Diocletian (AD 303), the "Great Persecution" targeted sacred books; edicts demanded their surrender for burning, yet hidden copies survived in caves and catacombs.

In the medieval era, the Byzantine text endured Islamic invasions and iconoclastic controversies. During the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (AD 1453), Greek scholars fled westward, carrying manuscripts that would fuel the Renaissance. Protestant Reformers faced similar fury: John Wycliffe (c. 1320–1384) translated from the Latin Vulgate (itself derived from Byzantine sources), but his Lollard followers were hunted as heretics. William Tyndale (1494–1536), martyred by strangling and burning for his English New Testament based on Erasmus's Greek, declared, "I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost." Foxe's chronicles detail how these persecutions, from Wycliffe's bones exhumed and burned in 1428 to the Marian persecutions (1553–1558) claiming 300 Protestant lives, only amplified the texts' spread. As truthischrist.com observes, each martyr's death sowed seeds for more copies, fulfilling Tertullian's (AD 160–220) words: "The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church."

Even in the 20th century, believers in Soviet gulags and Chinese house churches smuggled handwritten Bibles, echoing this legacy. The Dean Burgon Society, founded in 1978 to honor Burgon's defense of the Traditional Text, continues this fight, emphasizing how persecution purified the text like silver in a furnace.

The Lineage to the Textus Receptus and the King James Bible

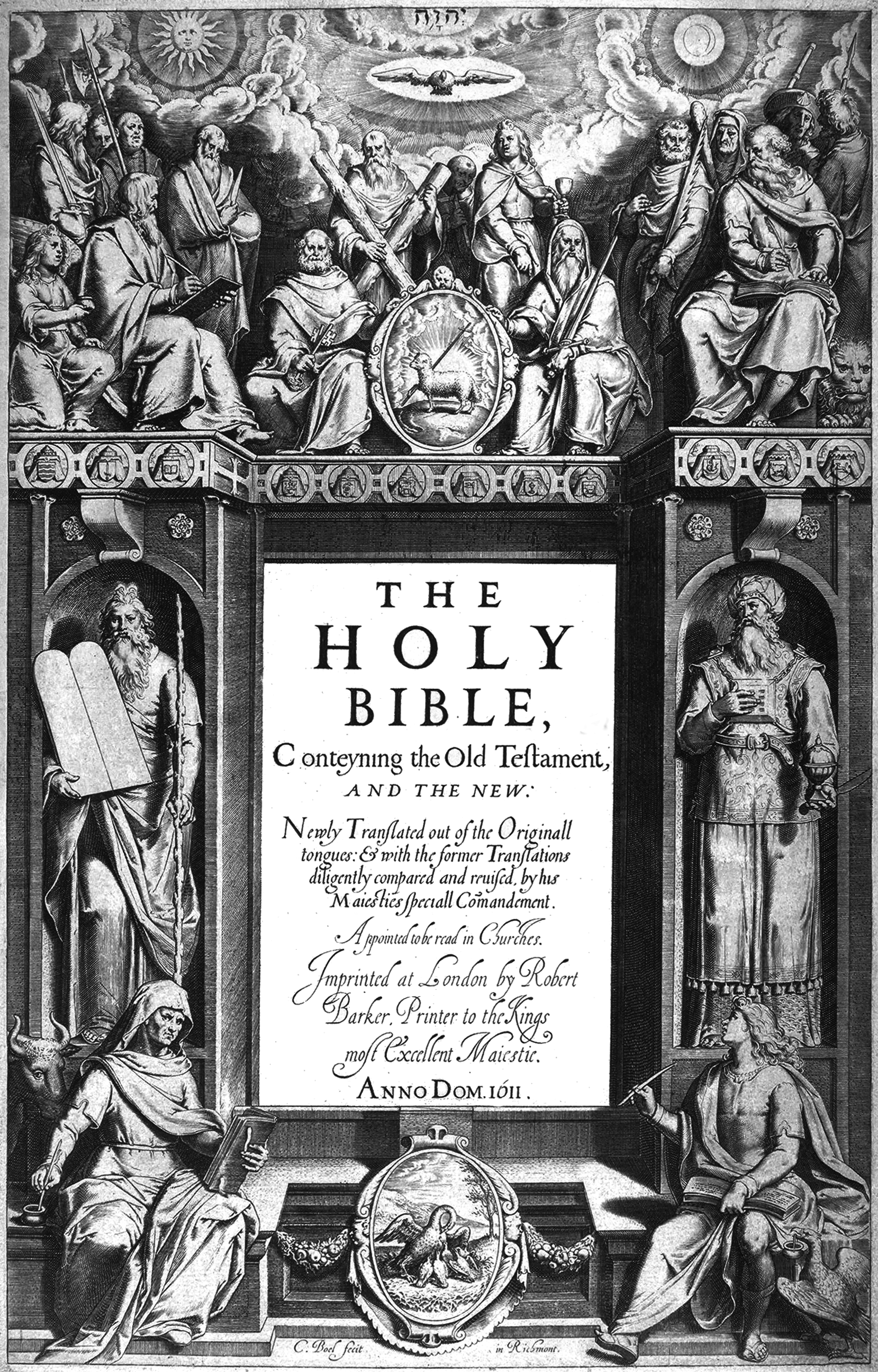

The path from ancient autographs to the KJV is a chain of providential editions. In 1516, Desiderius Erasmus, under pressure from printer Johann Froben, rushed the first printed Greek New Testament in Basel, Switzerland. Using a dozen Byzantine minuscules from the 12th–15th centuries (e.g., Minuscule 2 and 2814), Erasmus back-translated Revelation 22:16-21 from the Latin Vulgate to complete the Greek, but later editions corrected this to pure Byzantine readings. His five editions (1516–1535) formed the Textus Receptus ("Received Text"), so named by Robert Stephanus in his 1550 edition, which added verse divisions still used today.

Theodore Beza, Calvin's successor, refined it in 1582 and 1598, drawing from the Complutensian Polyglot (1514–1517), a Spanish project using additional Byzantine manuscripts. These editions, agreeing in 99.9% of readings per kjvtoday.net, were the foundation for Reformation translations: Luther's German Bible (1522), Tyndale's English (1526), and the Geneva Bible (1560).

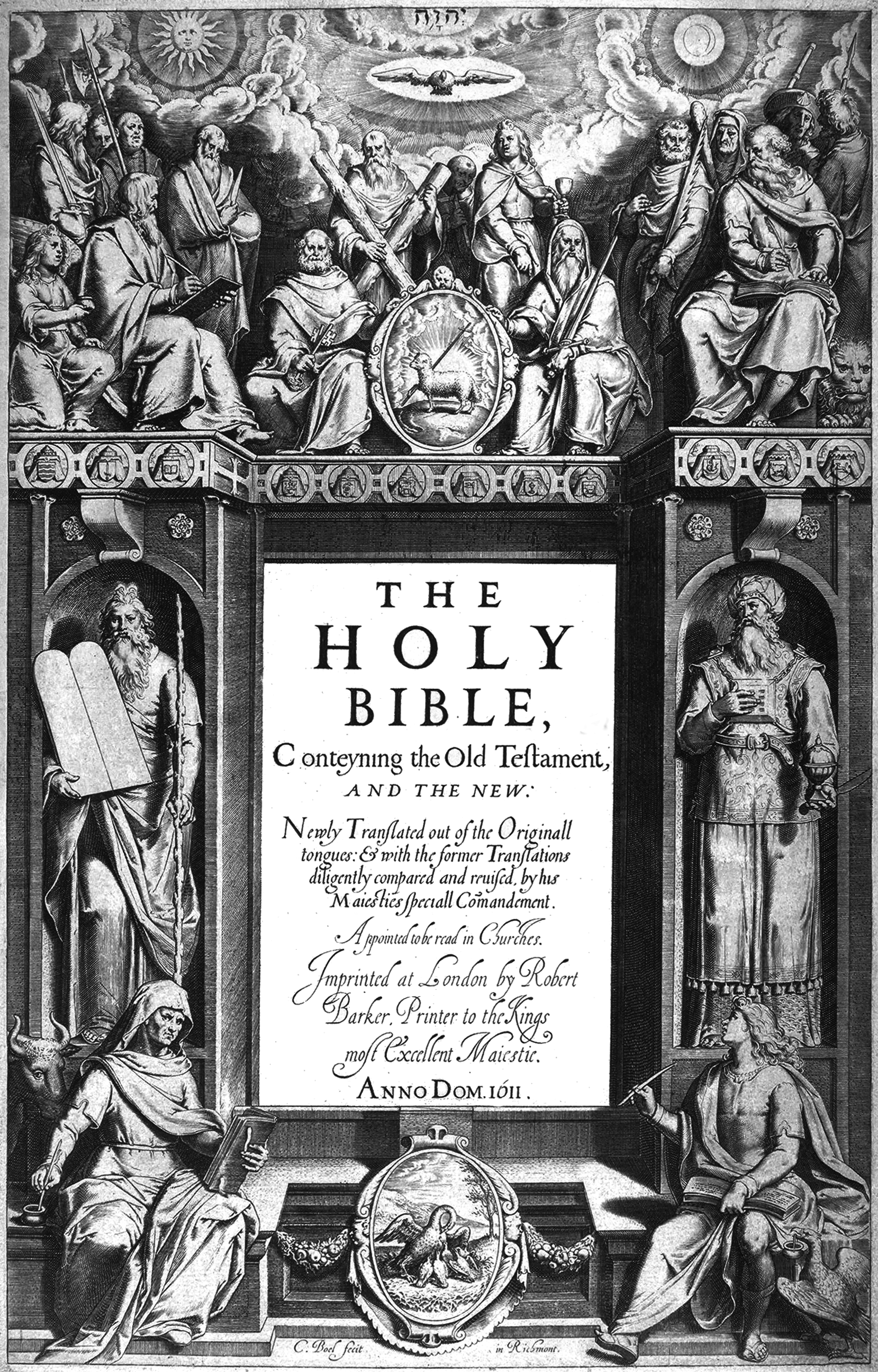

In 1604, King James I commissioned 47 scholars at Oxford, Cambridge, and Westminster to produce an English Bible "for the people." Dividing into six companies, they used the Bishops' Bible (1568) as base, consulting the Textus Receptus, Masoretic Text, and Septuagint only for clarification—not as authority. The KJV, printed in 1611 by Robert Barker, synthesized this heritage into majestic prose, with translators like Lancelot Andrewes and John Overall ensuring fidelity. As Jack McElroy details on jackmcelroy.com, the KJV's superiority lies in its alignment with the preserved majority text, avoiding "conjectural emendations."

Over 400 years, the KJV has been printed billions of times, influencing English literature and law, its words etched in the hearts of believers worldwide.

The Sheer Magnitude: Biblical Manuscripts vs. Historical Figures

The evidential support for the received texts dwarfs that for secular history. For Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars, only 10 manuscripts exist, the earliest from AD 900—900 years after composition—with 751 variants. Tacitus's Annals has 20 copies, the oldest from AD 850, 800 years removed. Yet historians accept these as reliable.

Contrast this: Over 24,000 total New Testament manuscripts (5,300 Greek, 10,000 Latin, 9,300 others), with the earliest fragments (Papyrus 52, John 18, c. AD 125) just 25 years from John's death. For the Old Testament, the Masoretic tradition includes 1,200 medieval manuscripts plus Dead Sea Scrolls confirming 95% identity over 1,000 years. This is God's words preserved as promised, not mere human records. Cold Case Christianity's J. Warner Wallace, a former atheist detective, notes the Bible's manuscript evidence is 1,000 times stronger than for Plato or Aristotle.

Papyrus 52, containing John 18, dated c. AD 125, one of the earliest New Testament fragments.

A Stark Contrast: The Frailty of Critical Texts

In sharp opposition, the "critical texts" like Westcott-Hort's 1881 edition, based on fewer than 50 manuscripts (primarily Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, both 4th-century uncials, at best, discovered in questionable circumstances), omit over 1,800 words and entire verses present in the Byzantine majority. Sinaiticus, "found" in a monastery wastebasket, contains corrections by 11 hands and Gnostic-like readings (e.g., Mark 16:9-20 absent). Vaticanus, locked in the Vatican since the 15th century, skips Hebrews 9:14–13:25 and Revelation entirely, with erasures suggesting tampering. Burgon called them "vile" for disagreeing in 3,000 places across 255 pages. Riplinger exposes their ties to occult influences, yielding "New Age" dilutions. With only 1% manuscript support, these texts rely on conjecture, not preservation—a house built on sand.

Sources