By the second century, these churches had produced the Italic Bible, a Latin translation from the Greek Received Text, dating no later than A.D. 157. Augustine himself praised it around A.D. 400 for its fidelity to the originals, stating it was "from the Greek tongue... rendered more faithfully and literally." This version, free from the corruptions later introduced in Jerome's Vulgate, was the liturgical Bible of the Waldenses, linking them unbroken to apostolic sources. The "Noble Lesson" (La Nobla Leyczun), a Waldensian confession from around A.D. 1100, declares their faith as that "which was from the beginning," opposing papal Rome since the time of Pope Sylvester under Constantine (A.D. 314–335). Waldensian historian Jean Leger (1669) affirms their doctrines dated to A.D. 120, with missionaries carrying pure manuscripts from Judean churches to northern Italy via the Syrian Church of Antioch and the Gallic Church.

Enemies of the faith unwittingly confirm this antiquity. Inquisitor Reinerius Saccho (13th century) admitted the Waldenses flourished around A.D. 600, predating Peter Waldo by 500 years. Jesuit Gretzer, in his anti-heretic treatise, struck out references to their pre-12th-century existence but left traces of their 600-year history. Theodore Beza, Calvin's successor, described them as "the seed of the primitive and purer Christian church," never yielding to papal superstitions. Bohemian traditions trace their roots to Paul's preaching in Illyricum Romans 15:19 and Titus in Dalmatia Titus 1:5. Even the Catholic Encyclopedia concedes claims of their establishment by Paul during his journey to Spain, though it dismisses them—revealing the discomfort with evidence that undermines Roman primacy.

This lineage fulfills Revelation 12:6, 14, where the woman (true church) flees to the wilderness for 1,260 years (A.D. 538–1798, per historicist reckoning), nourished by God's Word in alpine fastnesses. The Waldenses, as Montenses ("mountaineers"), embodied this, mingling with early nonconformists like Vigilantius (late 4th century), who preached against monasticism and image worship in Gaul, calling believers "insabbati" (Sabbath-keepers). Their continuity is no myth but a providential thread, woven through Paulician refugees from Armenia (7th century) who joined Albigenses and Waldenses in southern France and Piedmont, sharing identical doctrines and government.

Scriptural Theologies: Anchored in the Pure Word of God

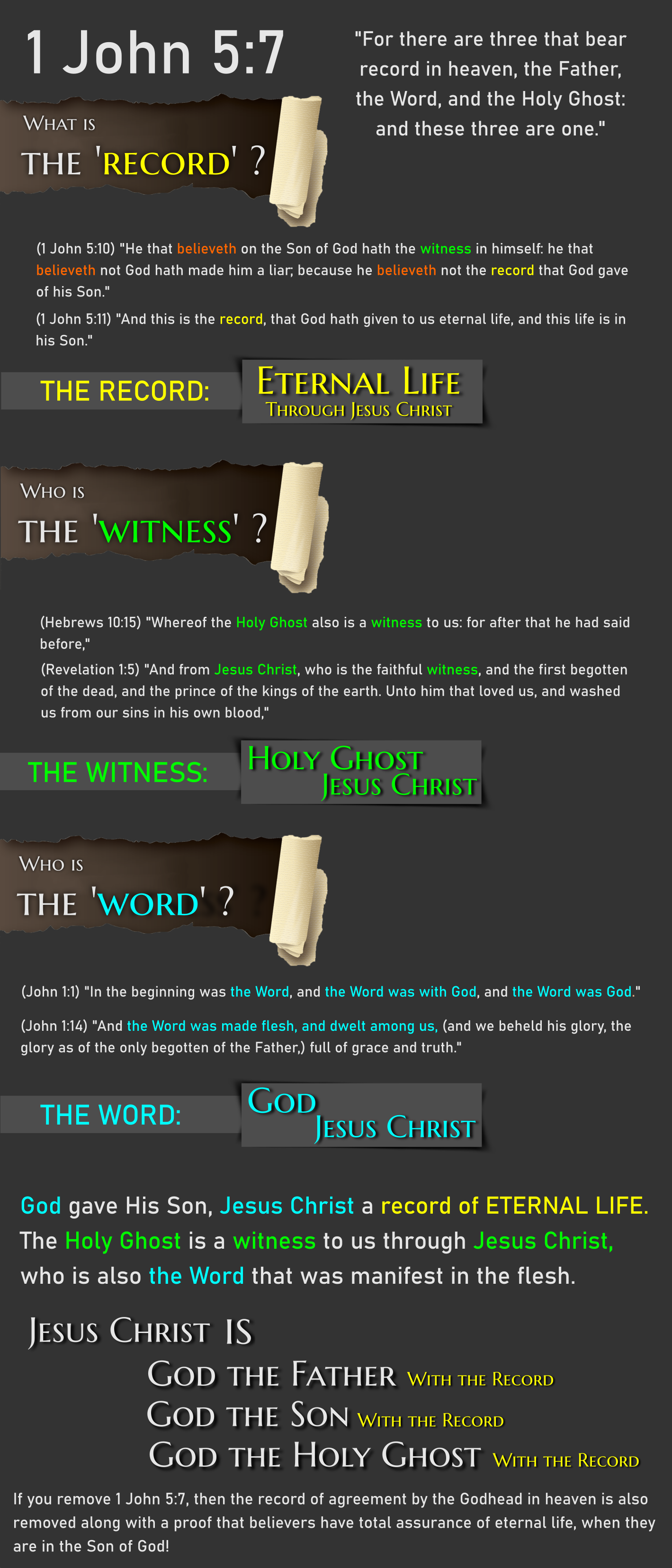

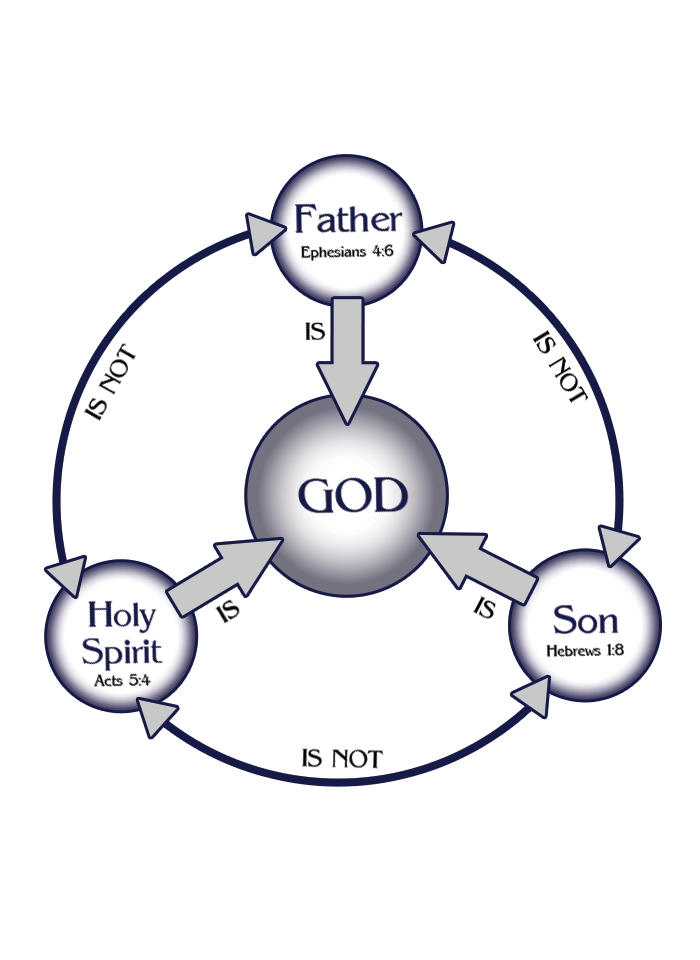

The Waldenses' theology was not speculative philosophy but the unadulterated exposition of Scripture, received "only what was written in the Old and New Testaments," rejecting papal "depravations through doctrines and glosses." Their confessions, such as the 1556 Angrogne declaration, affirmed plenary inspiration: 2 Timothy 3:16, "All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness." They viewed no prophecy as 2 Peter 1:20, "of any private interpretation", insisting on correction solely by the Word.

Key Doctrinal Examples

- Authority of Scripture Over Tradition: Against Rome's exaltation of councils and popes, they declared, "We do receive and admit no other rule of doctrine than the infallible word of God," citing Isaiah 8:20, "To the law and to the testimony: if they speak not according to this word, it is because there is no light in them." This fueled their rejection of transubstantiation, private masses, and saint veneration as Mark 7:7–8, 13, "traditions of men". In disputations, ministers like those at Angrogne countered unscriptural claims by demanding proof from Hebrew or Greek originals, as in their 1556 response to the president of St. Julian: "We live by the word of God... ready for correction if error be proved by Scripture."

- Salvation by Faith Alone: They taught justification by grace through faith Ephesians 2:8–9, "For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast", scorning indulgences and purgatory. The "Noble Lesson" proclaims Christ as the sole mediator 1 Timothy 2:5, with salvation John 5:39, "wholly in Him". Waldensian evangelism emphasized personal conversion, as in their training schools where youth memorized Romans 10:9, "That if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved."

- Baptism and Sacraments: They practiced believer's baptism Matthew 28:19–20, "according to the institution of Christ", rejecting infant baptism as unscriptural. A 1556 incident involved a father defending his child's baptism at Angrogne against rebaptism demands, citing Acts 2:38, "Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins." Sacraments were administered "duly" per New Testament pattern, without priestly mediation 1 Peter 2:9, "But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood".

- Sabbath Observance and Simplicity: As "insabbati," they kept the seventh-day Sabbath Exodus 20:8–11, opposing Sunday enforcement as papal innovation. Their lives embodied 1 Corinthians 14:33, "For God is not the author of confusion, but of peace, as in all churches of the saints," shunning oaths, dancing, and lewdness James 5:12; Ephesians 5:4. Poverty vows mirrored Matthew 10:9–10, but without monastic isolation—evangelists lived Genesis 3:19, "by the sweat of their brows", preaching two-by-two.

These doctrines, preserved in vernacular Bibles like the Olivetan (1535) and Diodati (1607), influenced Reformers: Luther consulted their Tepl German manuscript, and King James translators accessed six Waldensian versions. Their faith conformed to the Apostles' Creed and Ten Commandments, open to "correction from the Word of God," proving them no sect but the primitive church's remnant.

Persecutions: A Trail of Blood from Apostles to Alps

From apostolic shadows under Nero to medieval inquisitions, the Waldenses endured relentless papal fury, fulfilling Matthew 5:10–12, "Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness' sake." Early persecutions scattered Italic churches into Piedmont caves, but intensified under popes like Gregory I (A.D. 590–604), who burned their libraries and altered records to insert "Waldenses" as modern heretics. By the 12th century, despite claims of novelty, crusades targeted them as "Manicheans," though their doctrines were purely evangelical.

The Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) massacred thousands in southern France, with the Council of Toulouse (1229) banning lay Scripture possession to starve their faith. In Piedmont, the 1555–1561 war under Duke Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy epitomized horrors: armies of 6,000–7,000 Spaniards and Piedmontese razed villages, burning 1,000 Angrogne houses and slaying innocents. Foxe details the 1561 Tour Meadow assault, where 7,000 invaders assaulted three bulwarks; Waldensians, armed only with stones and slings, repelled them with miraculous losses—only two slain versus enemy cart-loads—after kneeling prayers: "Help us, O Lord!" Captain Bastian de Vergilia, mortally wounded, confessed, "God fighteth for them, and we do them wrong."

The 1655 Piedmont massacre, documented by Sir Samuel Morland, saw 4,000 Waldenses slaughtered in days, with women and children hurled from rocks. Inquisitor Jacomel (apostate monk) roasted ministers over slow fires, forcing women to carry faggots while accusing; one replied, "Ah, good women! I have taught you well, but you have learned ill." Charles and Boniface Truchet spoiled Riuclaret pre-dawn, burning captives alive. Yet, God intervened: earthquakes, tempests, and routs confounded foes, as in the Cluson River battle where Angrognians overthrew 120 soldiers without loss, dyeing the waters red. Total war dead: a mere 14 Waldensians, proving divine protection Psalm 91:7, "A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee."

These atrocities, exceeding pagan cruelties, targeted their Bible-centered faith, fulfilling Revelation 12:17, the dragon's wrath against "those which keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ."

Methodologies for Preservation: Caves, Copies, and Colporteurs

Faced with extermination, the Waldenses devised resilient strategies to safeguard Scripture and doctrine, embodying Proverbs 4:13, "Take fast hold of instruction; let her not go: keep her; for she is thy life." Their alpine terrain provided natural fortresses: high valleys like Angrogne, Lucerne, and Pragela hid assemblies in caves, where they sang Psalms and preached undetected. The College of the Barbs trained youth in memorization—entire books internalized—before university infiltration, sewing Scripture portions into hems for smuggling.

Hand-transcription was paramount: small, portable New Testaments in vernacular (pre-Reformation) circulated Europe via colporteurs—tradesmen and "poor of Lyons" who sold goods door-to-door, discerning hearers before sharing parchments. The Italic Bible's purity ensured doctrinal fidelity; Olivetan’s 1535 French version, edited by Calvin, stemmed from these manuscripts. Oral evangelism complemented: missionaries preached in markets, using Proverbs 11:30, "The fruit of the righteous is a tree of life; and he that winneth souls is wise." During famines post-1561, they carried goods "like ants," singing Psalms in retreat. Post-massacre recoveries, like Leger's 1655 collections, preserved texts in Cambridge University Library. Their motto, "Lux Lucet in Tenebris" (Light shines in darkness, John 1:5), guided quiet dissemination, influencing Wycliffe, Tyndale, and the KJV without state aid.

Refuting Catholic Lies: Dismantling the Waldo Myth and Heresy Slander

Catholic historiography peddles two core deceptions: (1) the Waldenses originated with Peter Waldo (c. 1170), a Lyonnais merchant turned preacher, making them a late medieval sect; and (2) they were dangerous heretics, akin to Cathari dualists, justifying inquisitorial genocide. These fabrications, propagated since the 13th century, aim to sever their apostolic roots and legitimize papal supremacy.

First, the Waldo myth crumbles under evidence. Waldo joined existing Vaudois groups, adopting their name post-1160; "Vallenses" predates him by centuries, twisted by papists like Gretzer to imply novelty. Reinerius Saccho dated their flourishing to A.D. 600; the "Noble Lesson" (A.D. 1100) predates Waldo, decrying Sylvester's corruptions. Beza and Leger affirm A.D. 120 origins, with Italic Bibles from A.D. 157. Even Catholic sources like the New Advent Encyclopedia admit pre-Waldo claims to Pauline founding, though dismissed as legend—yet Jerome's Vulgate (A.D. 382–405) corrupted the pure Itala to suppress this lineage. Waldo's movement was a revival within, not the genesis of, ancient churches; his excommunication (1184) widened the breach, but doctrines remained evangelical, not novel.

Second, heresy charges collapse: unlike Cathari dualism (good/evil matter-spirit split), Waldenses affirmed creation's goodness Genesis 1:31, rejecting ascetic extremes. They adhered to Catholic basics initially but diverged on Scripture's supremacy, earning papal ire. The 1229 Toulouse Council banned Bibles to silence their preaching, not dualism. Inquisitors like Jacomel were "whoremongers and extortionists," their trials mockeries—torture extracted false confessions, yet constants like Bartholomew (1556) confessed Christ unyieldingly before burning. Foxe exposes fabricated records: Gregory I systematically destroyed Waldensian histories, inserting "Waldenses" to portray them as 12th-century upstarts. Modern Catholic apologists, echoing Vatican II's ecumenism, recast them as "proto-Protestants" only after Reformation pressure, but evidences—from Augustine's Itala praise to Morland's 1658 eyewitnesses—prove them preservers, not innovators. As Bible.ca notes, their emphasis on preaching and Scripture rejection of papal authority made them targets, not heretics; crusades eradicated Cathari but reduced Waldenses through sheer resilience.

These lies, per Revelation 17:5–6, mark the "mother of harlots" drunk with saints' blood—yet truth endures, as Psalm 119:89, "For ever, O Lord, thy word is settled in heaven."

Conclusion: A Legacy of Light in the Wilderness

The Waldenses stand as a testament to God's faithfulness, bridging Paul's Italic sowing to Reformation reaping. Their persecutions forged unbreakable resolve; their preservation methods ensured Scripture's survival; their theologies, pure as KJV gold, refute Rome's shadows. In an age of misinformation, their story calls us to Jude 1:3, "contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints", knowing the gates of hell shall not prevail Matthew 16:18.